Everything Belongs Everywhere

- Ishita Lohani

- Dec 30, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 28

By Ishita Lohani

I walked behind Arvind. I felt like a timid figure. The Dhauladhar rose to our left, all white this December. My shoulders drew themselves in and I imagined a bend in my spine. I looked for the bent coconut trees that line the trails of Konkan. This knowledge – of still yearning for elsewhere, while Arvind walked only a little ahead of me – made me feel guilty. I sped up.

We had been arguing lightly since the morning – about pace, stops, and predictions of the weather. These arguments were less about the walk, perhaps more about how to move through things. How and how much to worry when there is no clear advantage to either speed or caution. I tried to impose less.

‘Tch! You haven’t been here in the past three years’, Arvind said. ‘The climate’s changed now, soil becomes too moist now’. His words fell heavy on me, they instead said, don’t tell me what to do after leaving me here for three years. I wanted to retort, but restrained myself. I felt anxious to change the subject. I thought to tell him about Amita, he’d always tell me I need to meet a girl.

The trail sloped upwards and the air thinned. At a sharp turn, the ground dropped suddenly. This turn had always scared me. I stopped and Arvind crossed without hesitation.

I braced myself to cross it and clutched to a root for support. Right at the threshold, I heard Arvind shout, ‘Juno! Check this!’ My attention faltered. My heart leapt out of my chest. I thought I’d fall off.

I crossed, said a prayer I’d learnt as a child, immediately resenting myself for still needing it. I walked ahead to find Arvind crouched on the ground.

He was holding some sort of sign. ‘What’s this’? I asked.

‘I don’t know. Some kind of medical thing?’

I took it from him. TRIAGE TAG was written on top. Two boxes were checked. Breathing - YES. Bleeding - NO. There was no name, no number on it.

‘It’s a triage tag’.

‘What’s a triage tag’?

‘A triage tag is basically like a priority thing. It is used during rescuing and emergency situations’, I told him.

He waited.

‘If it is red, that means top priority, usually lots of bleeding or breathing problems. Red means immediate attention. Yellow can wait. Green is stable.’

‘Oh’.

‘Yeah, and there is black too, means almost deceased, or really costly to save. So last priority’.

‘Oh, but this one doesn’t have black’. He handed the sign back to me for inspection. There was a white string threaded through a hole at the top. ‘Yeah, weird. Where did you find this?’

Arvind panicked, ‘Do you think someone was injured’? He looked up to me, still squatting on his toes. ‘And it was tied to this shrub. Here’, he pointed to a shrub I couldn’t identify.

‘No, I don’t think so anyone was injured–’, I handed the tag back to him ‘ –see it’s empty, no name and no bleeding even’.

Arvind seemed relieved by this. I was not. He sat down comfortably, with legs crossed and flipped the tag back and front, examining it.

‘How do you know this?’, he raised his head once again.

‘Too many emergency wards last year man’, I said, finally looking into his eyes.

‘It’s crazy you know this man’. It wasn’t. Yet, I felt useful.

I loomed over him for a minute, then wandered off searching the bushes looking for nothing in particular. I imagined the tag tied to something – a wrist, a person, an animal. I thought of the coast. I thought of Amita. I thought of my last rescue.

When I returned, I sat next to him. We’d arrived at some kind of silence.

‘This landscape doesn’t permit red casually’, he said, smearing his thumb on the red box on the tag. He then stood up.

We resumed our trek. We spoke about food, about the weather, about Renu Didi’s runner of a buffalo and for a minute I forgot I ever left.

‘I have found more things here. A lost goat once.’ Arvind mentioned. ‘It had a tag too. It chose me and I was very happy. But soon I grew irritated at the responsibility. And then I realized the goat wasn’t asking me anything. I let it follow me to the village. It grazed the front of my house for months. Then a shepherd took it. I watched from my roof while eating oranges under the sun. Didn’t intervene to its new fate.’ Still, he was walking an inch ahead of me. Then he turned and looked back at me.

I felt stripped with his gaze as if he could hear me think – was I the goat? I blurted, ‘Oh, okay’.

He slowed down, coming right beside me. He then put his arm across me. He gave me this shudder of a hug. Like a pat on the back, but warmer, sturdier. A pat sheds responsibility, the giver believes in the receiver’s strength. This was a transfer of strength.

‘Eating oranges under the winter sun, I tell you,’ Arvind said, animated now, ‘every time a phaank bursts into my mouth, it’s like an explosion in my mind’. I laughed. He laughed harder. ‘Yeah you know, light flashes, it’s so good, so good’. I laughed more. ‘Are, you don’t believe me? Tomorrow, we eat auraange my friend!’

‘You’re so stupid’, I said laughing. We walked for a while vocalising auraange. I felt forgiven.

I wanted to say something. Something honest. ‘That triage tag – something about the presence of things where they don’t belong’. I wanted to tell him I’ll be going back. I’ll tell him later.

He said, ‘Good. Very good. But let me tell you, everything belongs everywhere in this small world’.

I didn’t agree at first. I kept walking beside him with my eyes on the ground. ‘Okay’, I said, with a surety. A commitment to his belief. Something I was trying to find all day.

‘Okay then’..

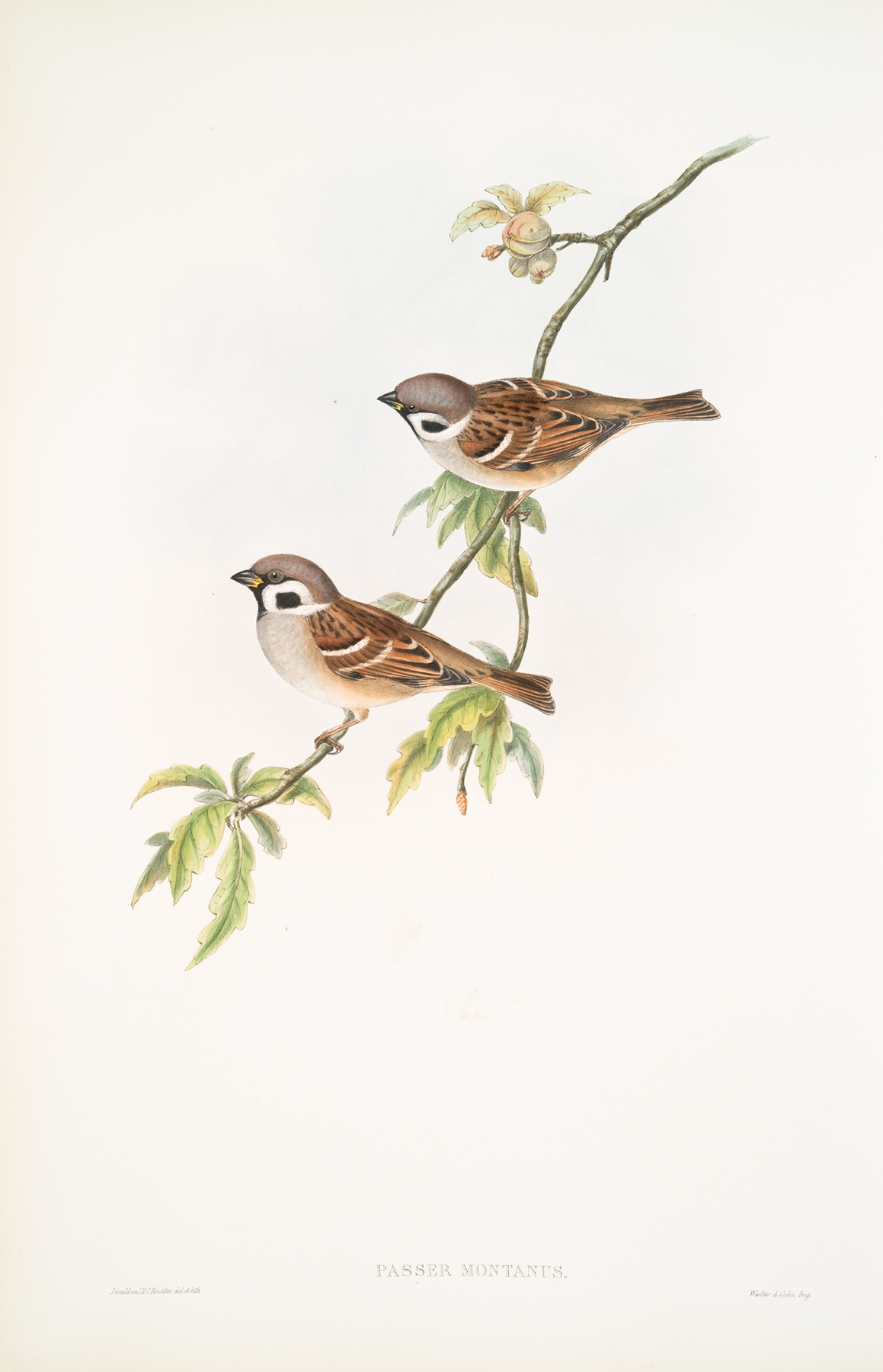

Image used: Google Gemini

.png)

Comments